Spaced repetition

2025-10-11Above is a heatmap of my Anki usage. It is updated in real time. I know, it is very far from perfect, and that there are more days skipped than not, but I will try to improve that in the future.

This way, I publicly commit: I, LS4, will never skip a day of Anki practice from 12th October 2025 until the environment requires me to do so.

By skipping, I mean not completing all the new cards (currently, 100 50 30 per day) and the cards for review.

By environment requirement, I mean a physical inability to practice on the day, or a special permission written here by my past self, if possible.

2025-12-27 UPD: I did not manage to do that. Most of the time I skipped because I felt asleep.

Why did I do that?

I really value how Nicky Case explained it. It actually was one of the many inspirations for this site.

But if you really somehow don’t want to read this masterpiece, here is a short summary:

Basically, we forget things. This fact is hard to argue with. I think I have already forgotten half of my school program, even though I haven’t even finished it yet.

A smart scientist, namely Hermann Ebbinghaus, found out that the rate of retention generally follows exponential decay:

This is sad. But the more we strain our brain with some information and the more we experience it, the slower the decay becomes.

This way we can learn better if we repeat things multiple times. Repetition is the mother of learning.

But Ebbinghaus shows us that the timing at which we repeat things is actually very important too. If we repeat things too early, there will be no strain for the brain. If too late - it will be just like learning the thing anew, which is too hard for us.

This is when Anki (or other repetition systems) comes into play. It calculates the perfect times when the strain is just right for you to learn the thing.

The learning itself happens with the help of flashcards. A flashcard contains two sides: a question, and an answer. You try to remember the answer to the question. Then, you flip the card. If you got it right, then you move on to the next card. If you got it wrong, then you move on to the next card as well. But Anki will remember to give you this card again soon.

Currently, Anki uses the new FSRS algorithm, which is an extremely complicated optimization model with 21 different parameters.

This may sound like overkill, but it does not really get in the way. This actually is a second thing that I like about Anki: the level of friction is minimal.

At least for me. I have a single deck with thousands of cards, which I just open, and mentally go through a simple algorithm:

def study():

while(len(cards) != 0):

card = cards.pop()

if (i_know(card)):

press(GOOD)

else:

press(AGAIN) # card gets returned to the stack at a later timeThat’s all. This is the entire learning process. No tests, no grading, no textbook re-reading. And it is scientifically proven to work better than most of the learning methods used in schools.

This way my daily card learning time is about 20-30 minutes per day. It is a bit more than the average user spends, but that is explained by my student life.

What do I learn?

Pretty much everything. My cards often look like this:

Question: Zipf’s law

Answer: When a list of measured values is sorted in decreasing order, the value of the n-th entry is often approximately inversely proportional to n.

I try to add cards for every Wikipedia or blog article I read and find important, my Foxford studies, German and Japanese words, programming concepts, or anything else I think I will need in my future life.

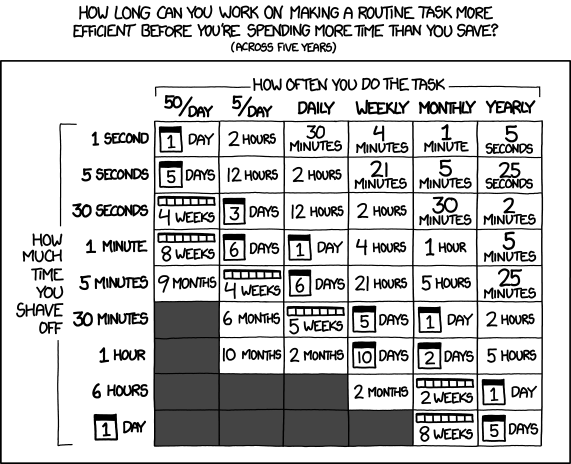

The general threshold is 2 minutes of life saved.

Rules for cards

These are the rules I try to follow when creating and studying my cards:

- Every card should be small (atomic).

- Every card should be connected (no orphan cards).

- Every card should be meaningful (learning something I care about).

- Learn and understand the topic before you memorize it.

- Build upon the basics.

- Reviews just before bedtime are a bit more efficient. But the effect is not big enough to change the habit, so I try to go through my Anki deck just before work and studying.

What if you forgot the answer?

You will remember it next time more easily, I promise. But how to memorize the card better if you made a mistake?

This is where many common memorization methods come into play, like the method of loci, mind maps, mnemonics, etc.

But improvement in spaced repetition software itself is also possible. Quoting Michael Nielsen:

How to best help users when they forget the answer to a question? Suppose a user can’t remember the answer to the question: “Who was the second President of the United States?” Perhaps they think it’s Thomas Jefferson, and are surprised to learn it’s John Adams. In a typical spaced-repetition memory system this would be dealt with by decreasing the time interval until the question is reviewed again. But it may be more effective to follow up with questions designed to help the user understand some of the surrounding context. E.g.: “Who was George Washington’s Vice President?” (A: “John Adams”). Indeed, there could be a whole series of follow-up questions, all designed to help better encode the answer to the initial question in memory.

But it sounds really hard to implement from a programming perspective. If the user is the one adding cards, then who will suggest cards that provide surrounding context? How to implement the newly added cards into the FSRS algorithm?

Luckily, we live in an AI era, so we may hope that someday there will be software that will be able to do that. Actually, it doesn’t even sound that hard to write, given the abundance and simplicity of LLM APIs. This is a startup idea, by the way. Go make it. I will be your first user.

Sources

https://gwern.net/spaced-repetition

https://cognitivemedium.com/srs-mathematics

https://www.supermemo.com/en/blog/twenty-rules-of-formulating-knowledge